GEORGES

BRAQUE

BRAQUE'S PLOUGH

... pushing a plough.

The Plough paintings come after Braque’s long engagement with the great Studio Series. The late Studios are the culmination of his life long effort to paint the vision of the space our eyes and even our souls roam in. His studio was filled with easels, pallets, portrait bust, plants, his own paintings and occasionally another human presence, Braque himself, maybe a model or a visitor. As he looks and paints he picks and chooses characteristics of form, lights and darks and flashes of color. He paints the tempo of how and where his eye travels and as the eye travels the space opens and gets deeper, more abundant. When the eye stops on any single element, even a particular texture you realize you have not really ever left the surface of the painting. It’s a kind of magic. Amidst all the studio paraphernalia there is a large bird often in motion. The bird gives a poetic element that characterizes the type of seeing/vision that takes flight and moves us. Braque said “the bird was a summing up of all my art it is more than painting.”

After the Studios, Braque moves in his last years to painting a series of horizontally oriented canvases of landscapes. They all seem in part to have been inspired by the turbulent landscapes of Van Gogh, but the hyper frenetic movement is turned down and turned inward to a more gently rolling layering, focused more on a caressing the earth itself with a layered undulating horizontal stacking. Many of these canvases are unusually exaggerated horizontals. These are not paintings of agricultural utility. The plough paintings are a look outside of his studio workplace a transition away from work, a move toward rest, horizontality. There are almost no vertical elements, no obvious stand in for human presence, no trees, no stalks they are dominated by the horizontal. It’s in the rolling movements of earth that we find the small and simple plough. Braque said in his notebooks "The plough rust and loses its usual meaning. "

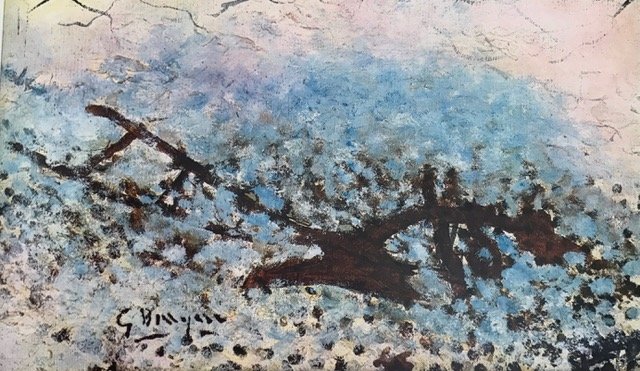

“The Plough” 1961 has no sky, no horizon; it is earth and plough, not really a landscape. It’s “plough” as protagonist. It has coloration that is unusually cool for Braque’s palate, a very cool light blue and white dominate with touches of light pink which only makes the cool colors even colder. At the top edge are what look like scratch marks, they resemble cracks in an ice-cold surface. The plough itself is a spatialized silhouette in coolish deep umber. This painting shivers.

The Plough, 1961. Oil on canvas. 7 3/4 x 13; not signed or dated. Private Collection

Still Life ll

“The Big Plough” 1960 has a pigment encrusted surface , light colors often layered over dark with dark showing thru. There is a sense of touch in the pigment as if holding mud in your hands and smearing it. Yellow that goes green, orange that goes to blue, purple gray, green gray, yellow lathered over deep blue black.There are patches of warm yellow gray, a bit of orange applied by pallet knife. The plow is turning up the pigmented earth. The plough itself is a dark silhouette and pierces not only the ground but the over all grid like quality of the paint patches. The plough is a deep space unto itself. The vigor in this painting is of a kind of burrowing.

The most striking of these paintings might be “Landscape with Somber Sky” 1955. Nothing in this painting negates anything said about the others, the extreme horizontality, the layering of mud like paint. But the unique drama and power of this painting is expressed in a nearly black sky. The sky is too dark for the land to be naturally as lighted as it is. The effect is unnatural. It is not like any landscape we may have witnessed. In 1956-57 Braque had painted what could have been the exact same scene, “Field at Colza” but in this case a golden field with a typical blue expanse of sky, much as we would expect to see in this part of France. In “Somber Sky “ the black sky is a shock and jolt to the ordinary. It is an overbearing, sky, declaring its presence, reminiscent of Munch’s Scream in its metaphysical howl. There is a plough present too. Burrowing into the lower right side of the painting while the sky rages. Braque’s friend the poet Jacques Pervert referred to these ploughs as,

“the skeletal plough

an earthly wreck”

The Big Plough

Landscape with Somber Sky, 1955

Field at Colza, 1956-1957

In the whole dark sky the only brightness is a gray silhouetted cloud that looks very much like the plough silhouette we have seen in the other paintings. Besides the visual rhyming of shapes we have added the rhyme of cloud/ploughed. The sky borne cloud reminding us of the alternate reading of the constellation big dipper also known as the large plough an ancient agricultural symbol in a vast sky. The poetry of these painting is multi layered and rich.

Nothing in the world Braque paints is static. Braque said “ To paint is not to depict.” It is useful to look at a Braque painting to find forces in opposition creating movement and a feeling of vividness. Braque’s paintings communicate feelings with visual, formal, painterly metaphors that transform the ordinary. What makes these last paintings so human and profound is the added element of poetic metaphor to the purely visual and formal.

If the bird was metaphor for the soaring movement of vision and spirit, The Plough, its torrid movement into the ground, is a profound metaphor for Braque’s sense of the end of his life. These paintings, in very basic human terms express the incessant unrest of seeing and being, and their endless mystery.